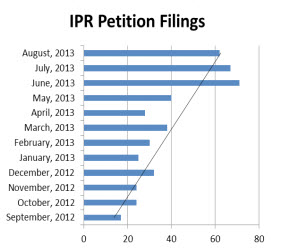

A year ago, on September 16, 2012, the America Invents Act introduced a number of powerful tools that enable a party to challenge the validity of an issued patent at the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO)—Inter Partes  Review (IPR), Covered Business Method Review and Post-Grant Review. The most popular tool has been the IPR.[1] The IPR procedure has altered the dynamics for challenging a patent’s validity, including adding a trial-like invalidity proceeding before three administrative law judges of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the USPTO. In its first year, IPR proceedings have experienced widespread industry adoption. As of September 3, 2013, there have been 476 IPR filings, and based on the increased rate of filings as depicted in the accompanying chart, the number of IPR filings will likely double in its second year.[2] The IPR procedure continues to gain momentum and should be considered as a part of any patent litigation strategy.

Review (IPR), Covered Business Method Review and Post-Grant Review. The most popular tool has been the IPR.[1] The IPR procedure has altered the dynamics for challenging a patent’s validity, including adding a trial-like invalidity proceeding before three administrative law judges of the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (PTAB) at the USPTO. In its first year, IPR proceedings have experienced widespread industry adoption. As of September 3, 2013, there have been 476 IPR filings, and based on the increased rate of filings as depicted in the accompanying chart, the number of IPR filings will likely double in its second year.[2] The IPR procedure continues to gain momentum and should be considered as a part of any patent litigation strategy.

IPR OVERVIEW

IPR was designed to be a cost-effective alternative to litigation. In fact, its legislative history states that the IPR process “will allow invalid patents that were mistakenly issued by the USPTO to be fixed early in their life, before they disrupt an entire industry or result in expensive litigation.”[3] To achieve this goal, IPR includes a number of features that make it an attractive alternative to litigation for defendants facing patent infringement lawsuits, parties facing the potential of a lawsuit and industry groups facing litigation by a patent assertion entity or the like.

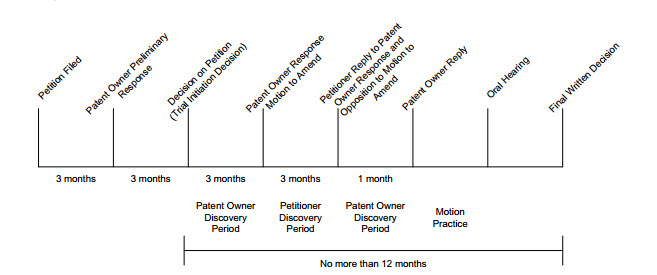

Expedited Timeline. One of the benefits of an IPR is the compact timeline.[4] Under the applicable statutory requirements and USPTO rules, an IPR must follow a tight schedule that will generally see a final written decision within 16 –18 months after the petition is filed compared to three–five years in district court. The following table provides an overview of the timeline for an IPR:

IPR: A YEAR IN REVIEW

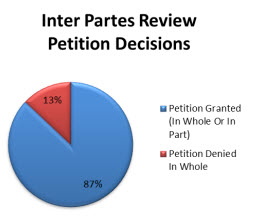

Majority of Petitions Granted or Partially Granted. There has yet to be a final written decision in an IPR on the merits;[5] however, the PTAB’s early decisions to grant or deny petitions provide a glimpse into what the future may hold. Through August 2013, 87 percent of petitions filed have resulted in institution of an IPR proceeding, meaning the PTAB found that there was a reasonable likelihood the petitioner (the party who filed the petition) will prevail as to at least one of the challenged patent claims. Importantly, in approximately 83 percent of those cases, the petition was granted for all of the challenged claims.

merits;[5] however, the PTAB’s early decisions to grant or deny petitions provide a glimpse into what the future may hold. Through August 2013, 87 percent of petitions filed have resulted in institution of an IPR proceeding, meaning the PTAB found that there was a reasonable likelihood the petitioner (the party who filed the petition) will prevail as to at least one of the challenged patent claims. Importantly, in approximately 83 percent of those cases, the petition was granted for all of the challenged claims.

The early decisions indicate the following as factors indicative of why petitions have been granted in the vast majority of cases:

- The standard for granting a petition requires only that there be a reasonable likelihood of success for invalidating at least one claim,[6] a fairly low standard as indicated by the high number of trials initiated to date.

- The PTAB construes claim terms using the broadest reasonable interpretation in light of the patent specification, which can result in a broad construction that facilitates a validity challenge. The standard for construing claim terms in litigation, by contrast, may yield a narrower construction.[7]

- There is an apparent lack of deference to the previous examination and any reexamination proceedings for the patent being challenged.[8]

- The petitioner is given an early advantage in IPR proceedings, as a petitioner may include expert reports with its petition whereas a patent owner may not provide its own expert reports until after the petition has been granted.

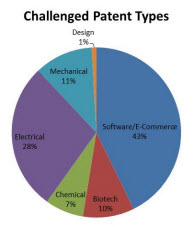

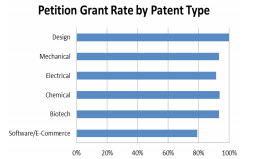

Software and Electrical Patents Are the Main Targets. IPR petitions have involved challenges to patents covering a wide range of technologies; however, software, e-commerce and electrical fields make up about 71 percent of the cases filed to date. Patents in the fields of software, e-commerce and electrical engineering are likely popular targets  for IPR as these types of patents historically have generated the highest damages awards and been more closely tied to non-practicing entities. Nonetheless, owners of software/e-commerce patents thus far have seen the most success in defeating petitioners’ bids for IPR proceedings, albeit by a

for IPR as these types of patents historically have generated the highest damages awards and been more closely tied to non-practicing entities. Nonetheless, owners of software/e-commerce patents thus far have seen the most success in defeating petitioners’ bids for IPR proceedings, albeit by a

slim margin.

Likelihood of a District Court Stay. Another factor encouraging petitions for IPR, particularly among those facing or already involved in litigation, is the prospect of obtaining a stay of the litigation pending resolution of the IPR. A decision to stay litigation lies within the sound discretion of the court, which involves considering whether a stay would unduly prejudice the patent owner, whether a stay would simplify the issues in the litigation and whether discovery is complete and a trial date has been set.[9] To date, many district court judges have shown a willingness to stay patent litigation in favor of an IPR.[10] Decisions granting a stay usually note the compact IPR timeline and the apparent judicial economy of allowing invalidity to be resolved in the first instance by the USPTO. Thus, filing an IPR petition early in litigation and ensuring that the IPR covers all of the asserted claims can increase the likelihood of obtaining a stay.

court, which involves considering whether a stay would unduly prejudice the patent owner, whether a stay would simplify the issues in the litigation and whether discovery is complete and a trial date has been set.[9] To date, many district court judges have shown a willingness to stay patent litigation in favor of an IPR.[10] Decisions granting a stay usually note the compact IPR timeline and the apparent judicial economy of allowing invalidity to be resolved in the first instance by the USPTO. Thus, filing an IPR petition early in litigation and ensuring that the IPR covers all of the asserted claims can increase the likelihood of obtaining a stay.

A stay has a very powerful effect on the concurrent litigation and may assist the petitioner in leveraging a favorable settlement. The ability to interrupt a district court case and halt the often substantial costs and fees associated with discovery, motion practice and trial preparation, while shifting to the more economical and constrained IPR procedure, can put power back into the hands of the petitioner. The discovery rules in an IPR provide an important constraint on burdensome discovery—it seems clear that any discovery that is desired beyond deposing witnesses who submitted affidavits and cross-examination of fact witnesses will be challenging to secure. Considering the high percentage of IPRs that have been instituted, the frequency with which stays of concurrent litigation have been granted and the cost savings associated with an IPR, it is not surprising that in its first year the IPR procedure has proven to be a valuable tool for petitioners, particularly those involved in concurrent litigation.

With the above backdrop in mind, the following strategic considerations should be considered depending on what side of the IPR you find yourself on. Indeed, the following considerations may place you in the position of celebrating the initiation of an IPR proceeding (petitioner), the defeat of a key aspect of an IPR petition (patent owner) or even the outright denial of a petition for IPR (patent owner).

STRATEGIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE PETITIONER

Pro-Petitioner Forum. With the indication of the IPR procedure being pro-petitioner, filing a petition for IPR may be advisable if you are involved in litigation where you believe the ultimate outcome turns on the validity of the asserted patent claims. The decision whether to file an IPR, however, is not easy and is very case-specific. First, a petitioner must have standing to file the petition[11] and there are limitations to the challenges that can be brought in an IPR.[12] Additionally, it is important to note that a final decision under IPR estops the petitioner from filing any invalidity proceedings in the USPTO, district court and ITC for any challenged patent claim on any ground that was raised or reasonably could have been raised in the IPR.[13] Finally, filing a petition for IPR places a lot of your litigation strategy outside of the courthouse and into the relatively untested hands of the PTAB. That being said, given the constrained costs as compared to litigation and the success rate of institution of an IPR, IPR appears to be an attractive option for potentially invalidating a troublesome patent.

With the above strategic considerations in mind, there are tactics that the petitioner can draw on to increase chances of a successful petition.

- Expert Testimony: The ability to use experts and the broad scope afforded claim terms appears to give petitioners a leg up in the IPR forum. Statistics support the use of an expert to solidify and underscore a petitioner’s positions on claim construction and arguments on anticipation or obviousness. In about 75 percent of the currently pending IPRs, the petitioner has filed an expert declaration with the petition. Indeed, petitions filed with an expert declaration have had about a 10 - percent greater chance of getting granted as compared to petitions filed without an expert declaration.

- Claim Construction: The PTAB has shown an inclination to side with the petitioner’s construction, providing that such construction is reasonable. Petitioners appear to have improved their chances of the petition being granted by about 15 percent by construing one or more claim terms and not simply reciting that they are entitled to their broadest reasonable interpretation.

- Focused Attack: When the IPR petition is focused on a small number of claims (e.g., less than fifteen claims) and a focused and well-developed number of grounds for invalidity (the average number of grounds granted is three) the petitioner seems to have had a slightly better chance of success.[14] The PTAB has been highly critical of excessive or cumulative grounds for invalidity, suggesting that petitioners taking this route waste valuable space in the petition.[15]

IPR Is Not for Every Accused Infringer. The decision whether to file a petition for an IPR is complicated and likely turns on the distinctions drawn above with respect to speed, limited scope, ultimate cost savings, potential stay of litigation and potentially increased leverage. Further, IPR is not for all patents or all cases. Some instances in which IPR may be a better option than pursuing invalidity in district court include

the following:

- Previously Cited Art: IPR proceedings see previously cited or considered art in about 66 percent of the cases, and the distinction between newly cited art and previously cited art does not appear to affect the PTAB’s decision as to whether to initiate the proceeding. The main reason for this is that unlike in district court litigation, there is no presumption of validity. So it makes little difference whether or not the art was previously considered. Thus, cases in which your strongest invalidating art was previously cited or considered should likely be pursued in the form of an IPR.

- Non-Practicing Entity: The IPR process lessens the burden on petitioners, especially when a stay of concurrent district court litigation is granted. In cases where the patent owner is a non-practicing entity (sometimes referred to as a “patent troll”), an invalidity challenge may be one of the primary mechanisms for the petitioner to obtain leverage. This is particularly true if the defendant is unable to assert its own patents against the plaintiff to generate leverage, as is often the case with non-practicing entities.

- Complicated Subject Matter: The PTAB is more accustomed to facing technically complex invalidity challenges. Thus, technically complex cases, such as cases in the software, e-commerce and electrical fields, may be more suited to the IPR forum.

STRATEGIC CONSIDERATIONS FOR THE PATENT OWNER

Time Is of the Essence. While the statistics seem to indicate that the IPR procedure is pro-petitioner, a patent owner has tools to help mitigate the petitioner’s advantage. The tools and timelines, however, must be aggressively managed, as the clock starts running as soon as a petition has been filed against your patent. Indeed, the patent owner must submit mandatory notice information a mere 21 days after the petition is filed.[16] Further, if a patent owner wishes to file a preliminary response, it is due just three months from the notice indicating the accepted filing date of the petition.[17] Also, the PTAB aims to render its decision whether to institute the IPR within six months of the filing date of the petition.[18]

Are You Prepared for Institution of the IPR Proceeding? Once the PTAB grants the petition, the patent owner has a mere three months to perform discovery; depose experts; craft expert declarations of their own; determine if, and if so what, claim amendments should be submitted; and formulate a comprehensive response that addresses each issue in the decision granting the petition in a mere 60 pages.[19] In addition, the patent owner has only 10 days to object to any evidence presented by the petitioner within the petition[20] and less than one month to provide a listing of any motions it intends to file during the proceeding.[21] Needless to say, it is vital that the patent owner and its counsel have their strategy planned in advance of the likely grant of the petition to comply with the short window afforded the patent owner.

Should You File a Preliminary Response? A preliminary response to a petition for IPR is optional. A patent owner’s decision whether to file a preliminary response is important, as there are many case-specific pros and cons to doing so (or not doing so). A preliminary response typically recites reasons why the petition for IPR should be denied. An important limitation of the preliminary response is that no new testimonial evidence (e.g., expert declarations) can be submitted with a preliminary response without the prior authorization of the PTAB.[22]

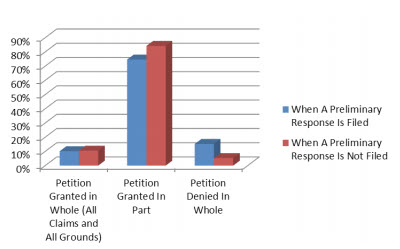

Importantly, the PTAB appears to be conducting a careful review of the arguments presented in the petition, whether or not a preliminary response was submitted. Indeed, current data, as evidenced by the chart above, shows that the PTAB’s rate for granting the petition is roughly the same regardless of whether a preliminary response is filed.[23] Filing a preliminary response does appear to result in a slight increase (about 10 percent) of outright denial of the petition altogether, but in those instances, it is possible that the patent owner chose to file a preliminary response in order to identify an obvious flaw in the petition.

whether or not a preliminary response was submitted. Indeed, current data, as evidenced by the chart above, shows that the PTAB’s rate for granting the petition is roughly the same regardless of whether a preliminary response is filed.[23] Filing a preliminary response does appear to result in a slight increase (about 10 percent) of outright denial of the petition altogether, but in those instances, it is possible that the patent owner chose to file a preliminary response in order to identify an obvious flaw in the petition.

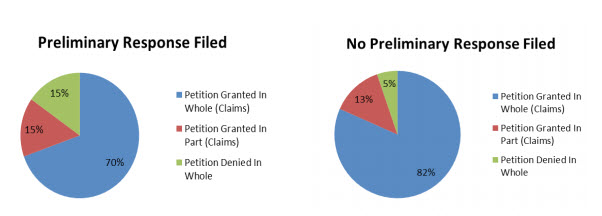

At first glance, this data would seem to suggest that there is little benefit to filing a preliminary response. However, this can be misleading, as although it has been shown that the PTAB appears to lean heavily toward granting a petition, the PTAB has little problem removing certain claims or challenges that lack merit.[24] The arguments in the preliminary response may help steer the PTAB in the right direction when determining which claims or challenges lack merit, thereby filtering the number of claims and challenges that will need to be addressed if the IPR is instituted. Indeed, with reference to the two charts below, current data shows that the PTAB granted the petition in part by instituting the IPR proceeding on less than all asserted claims 12 percent more often when a preliminary response was filed than when a preliminary response was not filed. Keeping the above in mind, it is important to remember the low standard for institution of the IPR—a reasonable likelihood that at least one of the claims challenged in the petition is unpatentable.[25]

Should You File Claim Amendments? The determination whether to file claim amendments is a case-specific one that includes a number of considerations, such as the likelihood of overcoming the validity challenges in the IPR, potential ramifications on infringement positions and potential ramifications due to the doctrine of intervening rights. Any motion to amend the claims of the patent must adhere to certain limitations and must be filed concurrently with the patent owner response.[26]

Alston & Bird has a robust patent litigation and prosecution practice with attorneys that specialize in each and both fields. Further, Alston & Bird has participated in many different post-grant proceedings, including IPRs, on both the petitioner side and the patent owner side. Click here to find a representative list of Alston & Bird’s post-grant proceeding experience.

For more information regarding inter partes review or any other post-grant-related issues, please contact Alston & Bird.

This advisory was prepared by Christopher Douglas and Patrick Kartes, members of Alston & Bird’s Intellectual Property – Patents Group, and Kirk Bradley and Steve Hemminger, members of Alston & Bird’s Intellectual Property – Litigation Group.

[1] To date, only a single Post-Grant Review has been filed and 53 Certified Business Method Reviews have been filed.

[2] Data source: https://ptabtrials.uspto.gov. Under 37 C.F.R. § 42.100(b), the director may impose a limit on the number of IPRs that may be instituted during each of the first four one-year periods. As of the date of this paper, the director has not set an official limit on the number of IPR filings.

[3] 57 Cong. Rec. S1326 (daily ed. Mar. 7, 2011) (statement of Sen. Sessions).

[4] The compact timeline for IPR proceedings is a key factor in courts granting stays for concurrent litigation.

[5] To date, the PTAB has issued two final decisions, but both pertained to procedural matters. See IPR2013-00212 (failure to respond to an Order to Show Cause); IPR2013-00134 (request for an adverse judgment). There has been one final decision on the merits in a Certified Business Method Review proceeding. In that proceeding, the PTAB found that all of the challenged patent claims were invalid for lack of patent-eligible subject matter under 35 U.S.C. § 101. SAP America, Inc. v. Versata Development Corp., Certified Business Method Review 2012-00001.

[6] See 37 C.F.R. § 42.108(c).

[7] In litigation, claims are generally given their “ordinary and customary meaning” as understood by a person of ordinary skill in the art in question at the time of the invention. See Phillips v. AWH Corp., 415 F.3d 1303, 1316 (Fed. Cir. 2005) (en banc).

[8] “In determining whether to institute or order [an IPR] proceeding . . . the Director may take into account whether, and reject the petition or request because, the same or substantially the same prior art or arguments previously were presented to the [USPTO].” 35 U.S.C. § 325(d) (emphasis added). For example, in IPR2013-00004, the PTAB instituted the IPR even though similar arguments had been considered during a previous reexamination proceeding.

[9] Cephalon, Inc. v. Impax Labs., Inc., 2012 WL 3867568, at *2 (D. Del. Sept. 6, 2012).

[10] The odds of the district court granting a stay seem significantly increased once an IPR is initiated by the PTAB. See, e.g., SoftView LLC v. Apple Inc., 1-10-cv-00389 (D. Del. Sept. 4, 2013, Order) (Stark, J.). At least one stay has been granted in an International Trade Commission (ITC) investigation. However, the constrained ITC timeline likely suggests that stays in the ITC will be the exception and not the rule.

[11] A petitioner (i) cannot have previously filed a civil action challenging the validity of a claim of the patent; (ii) cannot file a petition more than one year after the date on which it was served a complaint alleging infringement of the patent; and (iii) cannot file a petition if it is estopped from challenging the claims on the grounds identified in the petition. See 37 C.F.R. § 42.101. It is important to note that filing a declaratory judgment suit seeking a declaration of invalidity counts as a civil action and, thus, disqualifies one from being able to file a petition for IPR.

[12] A petition for IPR is limited to challenging claims of the patent on anticipation (35 U.S.C. § 102) and obviousness (35 U.S.C. § 103) grounds and only for prior art patents and printed publications. See 37 C.F.R. § 42.104.

[13] See 37 U.S.C. § 315(e); 37 C.F.R. § 42.73(d).

[14] Petitioners recently have been filing multiple IPR petitions for the same patent, apparently taking advantage of the perceived benefit of focused IPR petition filings. See, e.g., IPR2013-00185-IPR2013-00189.

[15] The petition for an IPR carries a 60-page limit. See 37 C.F.R. § 42.24(a)(i).

[16] 37 C.F.R. § 42.8(a)(2). The information for the mandatory notice is relatively straightforward; however, the short 21-day timeframe is important to keep in mind when selecting counsel to represent you.

[17] 37 C.F.R. § 42.107.

[18] The PTAB may institute an IPR proceeding on all or some of the challenged claims and on all or some of the grounds of unpatentability asserted for each claim. See 37 C.F.R. § 42.108. When the IPR proceeding is instituted, the PTAB usually will provide a scheduling order establishing due dates for all future actions in the IPR proceeding. See Office Patent Trial Practice Guide, 77 Fed. Reg. 48756, 48765 (Aug. 14, 2012).

[19] 37 C.F.R. § 42.120; 37 C.F.R. § 42.24.

[20] 37 C.F.R. § 42.64(b)(1).

[21] Office Patent Trial Practice Guide, 77 Fed. Reg. 48756, 48765 (Aug. 14, 2012).

[22] 37 C.F.R. § 42.107.

[23] According to the data, the petition is granted on all challenged claims and all asserted grounds about 10 percent of the time when a preliminary response is filed and about 11 percent of the time when a preliminary response is not filed.

[24] Current data shows that approximately 76 percent of the decisions on whether to institute an IPR proceeding deny at least one claim or one ground from the petition.

[25] 37 C.F.R. § 42.108(c).

[26] 37 C.F.R. § 42.121.

This advisory is published by Alston & Bird LLP to provide a summary of significant developments to our clients and friends. It is intended to be informational and does not constitute legal advice regarding any specific situation. This material may also be considered attorney advertising under court rules of certain jurisdictions.