With the onslaught of Affordable Care Act changes, health plan sponsors have much to think about lately. Given the number of other issues affecting them, plan sponsors may feel that HIPAA privacy and security is an issue they have already addressed. However, with the increased number of very public—and costly—data breaches involving protected health information (PHI) and increased enforcement power available to the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS), it is important for plan sponsors to do a “HIPAA double take” and make sure they are in compliance.

This advisory provides a HIPAA refresher and considers lessons learned from recent settlements between HHS and covered entities after HIPAA investigations. We conclude by discussing how health plan sponsors can protect themselves in this regulatory environment that is increasingly fraught with risk.

HIPAA Background

What information do the HIPAA privacy and security rules protect?

The HIPAA privacy and security rules govern PHI that is held or transmitted by a covered entity. PHI is individually identifiable information such as names, addresses, birthdays and Social Security numbers that identify the individual or for which there is a reasonable basis to believe can be used to identify the individual and that are used in conjunction with:

- The individual’s past, present or future physical or mental health or condition;

- The provision of health care to the individual; or

- The past, present or future payment for the provision of health care to the individual.

If the individually identifiable information does not relate to an individual’s health or health care, then the information is known as personally identifiable information (PII). PII is not protected by HIPAA but may be the subject of various state privacy regulations.[1]

Who is subject to the HIPAA privacy and security rules?

HIPAA requires two groups to comply with the privacy and security rules: covered entities and business associates. HIPAA defines “covered entities” as health plans, health care providers and health care clearinghouses. Health plans include health insurance companies as well as group health plans. One major exception to this rule is that self-insured group health plans with fewer than 50 participants are not covered entities if they are administered in-house. It is also important to note that health plan sponsors, unlike health plans, are not covered entities in and of themselves. Rather, the HIPAA privacy and security rules govern, in part, the flow of information from the health plan to the plan sponsor.

HIPAA defines “business associates” as third parties that provide services to covered entities involving the use or disclosure of PHI. Business associates must have written contracts with the health plan or other covered entity that establishes the scope of the business associates’ services and their obligations to the PHI accessed, used, created or maintained on behalf of that covered entity as part of those services.

Under the HIPAA privacy and security rules, covered entities have primary responsibility to protect PHI, but recent changes to HIPAA impose direct liability on business associates as well.

HIPAA Breaches and Plan Sponsor Responsibility

HIPAA breaches have gained significant media attention in the past year. What does this mean for plan sponsors? In addition to recognizing and mitigating breaches (see our prior advisory), plan sponsors should understand their responsibilities in the event of a breach affecting the plan.

Who bears the responsibility for a HIPAA notice in the event of a breach?

Most employer-sponsored health plans utilize multiple service providers (e.g., TPAs, PBMs) in order to provide coverage. In order to determine who bears the responsibility to issue a notice in the event of a breach, one must determine who the primary covered entity under HIPAA is.

If a plan is self-insured, the duty to issue a HIPAA breach notice lies with the plan. In this context, the group health plan is a covered entity and the third-party administrator (TPA) is only a business associate. Thus, in the absence of an agreement to delegate the HIPAA notification duty otherwise, the primary responsibility to notify lies with the self-insured plan, not the TPA.

If a plan is fully-insured because there are two covered entities (the insurer and the health plan), the duty to issue a HIPAA notice lies with the entity where the breach occurred.

What is the HIPAA duty to notify?

A HIPAA breach occurs when PHI is accessed or transmitted in a nonpermissible way. In the event of a breach, HIPAA requires that the covered entity notify each individual whose PHI was breached. If the breach affects at least 500 people, the duty to warn expands to notifying HHS. And if the breach affects at least 500 people in the same state, the duty to warn expands to include notice to prominent media outlets.

The notice must be made through first class mail and must contain information about the date of the discovery of the breach, the date of the breach itself if known, a description of the breach, information regarding how the individuals may protect themselves, information regarding what the covered entity is doing to mitigate the problem and contact information for the covered entity. The covered entity must deliver notice to the affected individuals without unreasonable delay and in no event later than 60 days after discovering a breach.

In contrast to a covered entity, a business associate’s only responsibility under HIPAA is to notify the covered entity of a breach. A business associate is not responsible for providing notice to affected individuals, HHS or the media. And while a business associate may assume the notice obligation by contract, the covered entity would remain liable for the business associate’s notice failures.

Increased Potential of HIPAA Penalties and Increased Settlements

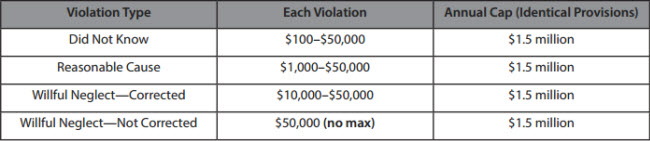

In addition to the threat of HIPAA breaches, plan sponsors should also be aware of HHS’s increasing authority when a HIPAA breach or other mistake has occurred. Among other changes, HHS’s 2013 HIPAA regulations implementing the HITECH Act (known as the “Omnibus Rule”) increased the potential penalties available to HHS for HIPAA violations.[2]

As a result, HHS has more power in settlement negotiations with covered entities during an investigation.

In addition, over the past decade, HHS has also increased the number of HIPAA privacy investigations. HHS’s historical numbers indicate that the total number of investigations has increased dramatically—from less than 5,000 in 2004, to between 8,000 and 9,000 from 2009 to 2013, to over 14,000 in 2013.[3]

This increased number of investigations, combined with HHS’s increased penalty ceilings, has resulted in an increasing number of large settlements with various covered entities. For example, in May 2014, HHS announced the largest HIPAA settlement to date: $4.8 million across two connected entities, New York and Presbyterian Hospital and Columbia University. In fact, the past three years have seen several multimillion-dollar settlements between HHS and covered entities. These include:

- Affinity Health Plan: $1,215,780 (2013)

- Alaska Department of Health and Human Services: $1.7 million (2012)

- Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary/Eye and Ear Associates: $1.5 million (2012)

Settlement agreements published by HHS make clear why, in addition to financial penalties, entities would do well to avoid HHS’s attention. HHS frequently imposes tough restrictions on covered entities, including requiring implementation and/or progress reports to HHS, thorough documentation of compliance efforts, workforce retraining, revisions to policies and procedures, and periodic risk assessments and risk management plans. These often go beyond the scope of HIPAA’s generally applicable requirements and subject the covered entities to HHS’s watchful eye for an extended period of time. Even in cases when financial penalties are moderate, HHS does not let covered entities off lightly after a breach or other complaint. Thus, covered entities are much better off complying from the beginning.

What is HHS looking for in investigations?

Entities looking to understand HHS’s enforcement priorities have a wealth of information available to them in guidance and published settlement contracts with covered entities. For example, HHS has stated that historically, its investigations have focused on:

- Impermissible uses and disclosures of protected health information;

- Lack of safeguards of protected health information;

- Lack of patient access to their protected health information;

- Lack of administrative safeguards of electronic protected health information; and

- Use or disclosure of more than the minimum necessary protected health information.[4]

This provides covered entities with a useful roadmap of what HHS is likely to look for in an investigation: situations where PHI is vulnerable to use or disclosure (or has, in fact, been improperly used or disclosed).

In addition, recent settlement agreements with various covered entities reveal the specific circumstances that have led them into trouble—often quite expensive trouble. A notable aspect of recent HHS settlements is that while some instances are somewhat flagrant (e.g., intentionally releasing PHI to the media, dumping patient records in public locations), many of the incidents settled by HHS could happen to any employer or health plan. For instance, several involve stolen electronic media such as flash drives or laptops. Another major theme is unintentional IT security lapses, such as unsecured servers or malware. Finally, HHS has also settled several cases related to improper disposal of PHI. Plan sponsors should be aware that these incidents can easily happen in a typical workplace, but HHS has little sympathy for entities that did not address the risk in advance.[5]

HHS’s settlements are also helpful in that they illustrate HHS’s reasoning for sanctioning covered entities. One theme that occurs in almost every settlement agreement is the failure to demonstrate a thorough analysis of the risk posed by PHI—usually electronic PHI—on an ongoing basis (in particular, potential risks with portable devices), failure to incorporate this information in a risk management plan and/or the failure to account for particular, foreseeable risks. Entities are also expected to conduct routine system reviews to ensure that potential risks are handled in a timely manner. HHS has also focused on the failure to address basic IT risks and/or implement technical safeguards and basic security measures, such as encryption, for electronic devices. More generally, it has criticized the lack of written policies and procedures (as a whole, or for a specific issue) and the failure to follow these written procedures. Finally, another major theme is the failure to provide adequate HIPAA training to staff. Health plans should be aware of these issues and make sure that they have been adequately addressed, in writing and in practice.

These settlements also illustrate the importance of involving multiple types of professionals, such as benefits personnel, IT experts and informed legal counsel, all of whom will have critical, but different, knowledge needed to protect the organization. For example, covered entities need to be aware of the physical and electronic locations of PHI, IT security strengths and weaknesses and risk areas (particularly in unexpected places, e.g., PHI remaining on copier hard drives). Without input from across the organization, entities may miss a critical vulnerability of the privacy or security of PHI.

Finally, while many of the recent settlements involve health care providers, HHS has also settled investigations with health plans, such as health insurers. In addition, it is important to note that many of the issues that arose with providers (e.g., stolen laptops, IT security lapses) could easily occur with employer-sponsored health plans. Thus, health plan sponsors should not assume that only health care providers, or large entities, are subject to HHS’s scope.

What does this mean for plan sponsors?

The recent instances of high-profile HIPAA data breaches and enforcement activity are a good reminder for employer-sponsored health plans to brush up on their knowledge of the HIPAA privacy and security rules. The fact that many covered entities were punished for violations that would not seem egregious to many plan administrators indicates that HIPAA issues can happen almost anywhere if the proper precautions are not taken. In addition, while a data breach may, to a certain extent, be outside of the control of a plan sponsor, there are still a number of steps sponsors may take in order to protect themselves.

How Can Plan Sponsors Protect Themselves?

- Ensure that their HIPAA privacy and security policies and procedures, Notice of Privacy Practices and Business Associate agreements are in place, up-to-date and followed in practice.

In addition, they should periodically perform risk assessments and risk management plans to identify and address vulnerabilities where violations of HIPAA may occur. For more information about risk assessments, please see our prior advisory. - Examine your contracts for PII provisions.

Because HIPAA does not protect PII, there is no federal HIPAA duty to notify individuals if there is a PII breach rather than a PHI breach. However, some states have privacy statutes that do regulate PII. To account for this, you should work with your business associates and other vendors to establish an appropriate protocol for dealing with PII breaches as well as PHI breaches. - Examine your contracts with business associates and other vendors for HIPAA notification provisions.

Ideally, your agreements should specify the responsibilities of both the plan and any vendors in dealing with a HIPAA or state data breach. The responsibilities should be determined in conjunction with the liability and indemnification provisions of the agreement. - ERISA fiduciaries should keep a record of all acts and considerations taken in connection with data breaches.

If your employer-sponsored plan is an ERISA plan, its fiduciaries have duties that lie beyond the reach of HIPAA. ERISA plan fiduciaries have a duty to act for the benefit of the individuals covered under the plan. In the context of a data breach, the ERISA duty to act is an additional duty to the HIPAA duty to notify. While ERISA fiduciaries must comply with the HIPAA duty to notify, they should also take additional affirmative steps regarding their duty to act in the event of a data breach. This should involve creating and maintaining a plan of action, reviewing health insurance issuer and TPA agreements and letting participants know what precautions you have taken on their behalf.

If you have any questions about HIPAA preparedness, please reach out to your Alston & Bird attorney, or any of the attorneys listed on the next page.

[1] HIPAA’s overlap with state law is important to take into account as we see more and more courts contract the scope of ERISA preemption, thus exposing plan sponsors to more state laws.

[2] For an overview of the Omnibus Rule’s major changes that affect health plan sponsors, please see our prior advisory: New HIPAA Omnibus Rule: Issues for Employer Plan Sponsors and Group Health Plans.

[3] HHS, Enforcement Results by Year, available at http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement/data/historicalnumbers.html. HHS has not provided numbers past 2013.

[4] HHS, Enforcement Highlights, August 31, 2015, available at http://www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement/highlights/index.html.

[5] These, and other HIPAA settlements, can be found at www.hhs.gov/ocr/privacy/hipaa/enforcement/examples.

This advisory is published by Alston & Bird LLP’s Employee Benefits & Executive Compensation practice area to provide a summary of significant developments to our clients and friends. It is intended to be informational and does not constitute legal advice regarding any specific situation. This material may also be considered attorney advertising under court rules of certain jurisdictions.