While most of the attention in the EU data landscape in late 2015 and early 2016 was focused on the Schrems decision, negotiations regarding the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield and passage of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), the EU also passed a new directive that could have significant impact on U.S. and multinational companies operating in Europe: the Network Information Security Directive (“NIS Directive”).[1] The NIS Directive will have significant implications for cyber preparedness and compliance issues, both for companies providing “essential services” and “digital service providers.” Many companies will be surprised to learn that they are digital service providers subject to the member state laws passed to implement the NIS Directive.[2]

What Types of Companies Are Subject to the NIS Directive?

Providers of essential services

The NIS Directive covers two categories of service providers. The first category is operators of “essential services.” This category will mostly apply to companies largely situated within the EU and will likely have less direct applicability to multinationals with operations in Europe. A company is an operator of essential services if: “(a) an entity provides a service which is essential for the maintenance of critical societal and/or economic activities; (b) the provision of that service depends on network and information systems; and (c) an incident to the network and information systems of that service would have significant disruptive effect on its provision.”

Member states are required to put forth a list of providers of essential services within six months after transposition of the NIS Directive into national legislation. The NIS Directive includes a table that details the types of companies it would treat as essential service providers, and not surprisingly, they include industries such as energy suppliers, transport service providers, large financial institutions, utilities, health care providers and providers of digital infrastructure (i.e., Internet exchange points, domain name system service providers and top-level domain name registries).

Digital service providers

The more surprising aspect of the NIS Directive is that its provisions also apply to certain “digital service providers.” There are three main categories of digital service providers: online marketplaces, online search engines and cloud computing services. In contrast to the requirement for member states to identify providers of essential services, member states will not be required to publish lists of companies considered digital services providers (nor would it be possible for them to do so given the breadth of the definition). Online companies will have to determine for themselves whether they are digital service providers and thus subject to security and notification requirements. Notably, however, the NIS Directive generally exempts micro- and small enterprises—i.e., companies employing fewer than 50 persons whose annual turnover and/or balance sheet total is less than €10 million—from its compliance requirements.

Online marketplaces

An “online marketplace” is defined as “a digital service that allows consumers and/or traders … to conclude online sales and service contracts with traders either on the online marketplace’s website or on a trader’s website that uses computing services provided by the online marketplace.” This is an extremely broad definition that could capture companies ranging from the largest e-commerce providers to small single product/service companies offering services through their websites (to the extent that such companies do not fall within the micro- and small-enterprise exclusion). It includes marketplaces that engage in B2C as well as B2B transactions. Curiously, app stores are deemed to be in scope, but price-comparison websites are not.

Online search engines

An “online search engine” is defined as “a digital service that allows users to perform searches of in principle all websites or websites in a particular language on the basis of a query on any subject in the form of a keyword, phrase or other input; and returns links in which information related to the requested content can be found.” It is clear that large search engines such as Google and Bing will fall within this definition. The NIS Directive does clarify, however, that search engines within a particular site will not be subject to the directive.

Cloud computing services

The third and perhaps broadest category of digital services covered by the NIS Directive—and the one that will potentially provide the most surprises—are cloud computing services. A “cloud computing service” is defined as “a digital service that enables access to a scalable and elastic pool of sharable computing resources.” While there is guidance on the meanings of “computing resources,” “scalable” and “elastic and sharable,” this definition could, on its face, apply to services provided by a wide range of companies and undertakings. For example, many application service providers/software as a service (SaaS) providers could easily be deemed to provide a “scalable and elastic pool of sharable computing resources.” Additionally, companies providing public, private and hybrid cloud services may also be within the scope of the NIS Directive based on this definition.

Which Member State’s Law Applies?

A key issue is which member state’s law will apply to companies that find themselves within the scope of the NIS Directive. Of course, providers of essential services will not confront this issue, as they will be identified on the roster published by the applicable member state. A digital service provider will be subject to the law of the member state in which it has its “main establishment,” which will typically be the member state where a provider’s “head office” is located. Although it is intended that only one member state have supervisory jurisdiction over a digital service provider, the location of the provider’s main establishment may be unclear for companies that have operations in multiple member states.

The more interesting question is whether a digital service provider that is not established in a member state, but still provides services within the EU, is subject to the NIS Directive at all—and if so, which member state’s law applies to that company. Where a digital service provider is not established in a member state, but still provides services within the EU, the directive requires the company to appoint a representative in “one of those Member States where [its] services are offered.”

This raises significant jurisdictional and application-of-law issues for U.S. and other companies based outside the EU that offer products and services widely available within the EU. Unlike other EU regulations on jurisdiction, the NIS Directive does not contain clear criteria for determining when non-EU-based providers have become active in the EU to such a degree that would bring them in-scope and require them to designate an EU representative. Instead, the NIS Directive lists factors not unlike a U.S.-style “minimum contacts” analysis, such as whether a company’s website is in a member state’s local language and whether that company’s website permits ordering in a member state’s local currency.

To the extent an EU representative must be appointed, she should be appointed by “written mandate” and be required to conduct breach incident reporting (as is also the case under the GDPR). As a result, online marketplaces, search engines and cloud service providers should take into consideration both NIS and GDPR compliance responsibilities when appointing European representatives and outlining their tasks and obligations.

What Cybersecurity Standards Are Imposed by the NIS Directive?

While the NIS Directive is intended to achieve a “high common level” of network and information security across the EU, it does not provide an overly prescriptive cybersecurity regime or protocol. Those subject to the NIS Directive are required to adopt “appropriate and proportionate technical and organisational measures.” Digital service providers are further required to ensure a level of security appropriate to the risk posed in offering covered services, taking into account the following elements:

- Security systems and facilities.

- Incident management.

- Business continuity management.

- Monitoring, auditing and testing.

- Compliance with international standards.

These requirements are, of course, quite general and—unlike ISO Standards, COBIT Standards or the NIST Cybersecurity Framework—do not offer precise guidance on appropriate measures or process. In the interest of harmonizing reporting requirements, the NIS Directive’s recitals state that the European Commission “should” issue more detailed provisions on digital service providers’ notification requirements and the procedures associated with them.

The directive provides for “minimum harmonisation” and allows member states to pass laws that achieve a higher level of cybersecurity than set forth in the NIS Directive itself. National systems would need to conform with the directive’s requirements, but member states may impose stricter requirements on operators under their jurisdiction. The risk is that, not unlike the situation under the current Data Protection Directive, companies find themselves confronted with varying and diverging cybersecurity standards.

Breach Notification Requirements Under the NIS Directive

The other interesting aspect of the NIS Directive is the establishment of yet another EU-wide requirement for companies to notify public authorities in the aftermath of a security breach. Those subject to the directive are required to notify any incident having a “substantial impact” on the provision of a covered digital service, or having a “significant impact” on the continuity of an essential service. Although the European Commission may adopt more specific rules on notification, the directive itself provides that notification should be made “without undue delay” to the national competent authority responsible for network and information security in the sector concerned or to the national Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT). CSIRTs are national bodies to be established under the directive that will monitor and respond to security incidents at the national level and coordinate on security incidents that may have a cross-border impact.

The NIS Directive provides some guidance to digital service providers regarding whether the impact of a cyber incident is substantial and thus triggers notification. The directive provides that covered entities should consider (1) the number of users affected by the incident, in particular users relying on the service for the provision of their own services; (2) the duration of the incident; (3) the geographical spread of the area affected by the incident; (4) the extent of the disruption of the functioning service; and (5) the extent of the impact on economic and societal activities. These may serve as valuable guiding principles as companies struggle with their potential notification obligations after a security incident.

Overlapping Breach Notification Requirements Under Other EU Legal Acts

The NIS Directive’s breach reporting requirements are independent of notification requirements contained in other EU legislation. As a result, the potential for overlapping notification requirements exists, in particular with requirements contained in the GDPR and the ePrivacy Directive.

NIS Directive breach notification requirements

The NIS Directive requires essential service providers to notify the competent national authority whenever an incident occurs that has an actual, adverse and “significant impact on the continuity of the essential services” they provide; digital service providers must notify the authority of any incident having an actual, adverse and “substantial impact on the provision of” certain digital services enumerated in annexes to the NIS Directive. These kinds of incidents may, but need not, involve the unauthorized disclosure of personal data.

Breach notification requirements under the GDPR and ePrivacy Directive

In contrast, the GDPR and ePrivacy Directive require notifications whenever “personal data breaches” occur, i.e., “a breach of security leading to the accidental or unlawful destruction, loss, alteration, unauthorised disclosure of, or access to, personal data.” Personal data breaches may, but need not, affect essential service providers or digital service providers, or involve significant disruptions to their IT systems.

Notification exemptions under the NIS Directive

To the extent that these reporting obligations potentially overlap, the NIS Directive exempts NIS-governed entities from multiple breach notifications to some extent. Article 1(7) of the NIS Directive exempts NIS-governed entities from their duty to report NIS-relevant “incidents” to the extent these fall under another EU regulation with a breach notification requirement that is “at least equivalent in effect.”

Moreover, Article 1(3) exempts otherwise NIS-governed entities from breach reporting to the extent they are companies that provide “public communication networks or publicly available electronic communications services” governed by Articles 13a and 13b of Directive 2002/21/EC. This exemption effectively removes telecom and web-based communications companies from NIS breach-notification duties because such companies are generally already required to report security breaches, usually to national telecom regulators. This is also the approach taken by recent German national legislation passed in anticipation of the NIS Directive designating telecom companies as “critical infrastructure,” but exempting them from general breach-reporting requirements because they are subject to equivalent notification requirements under telecom-specific legislation.[3]

Overlapping requirements

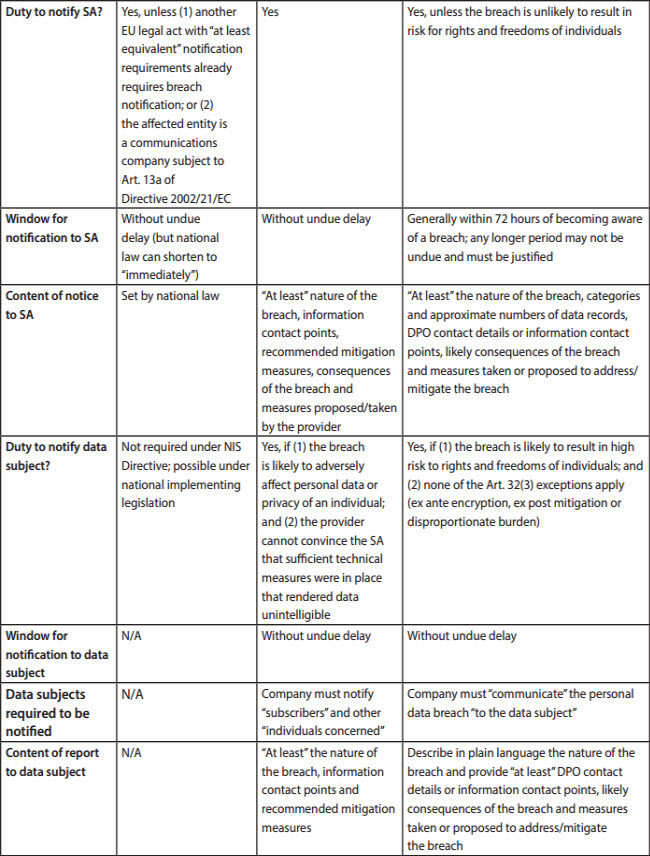

The potential for overlapping reporting requirements requires companies to be very organized in advance to determine whether they are a covered entity under various EU legal acts, what the harm threshold for a breach report is, the circumstances under which breach reports are due to Supervisory Authorities (SAs) and individuals, and the content of each report due.

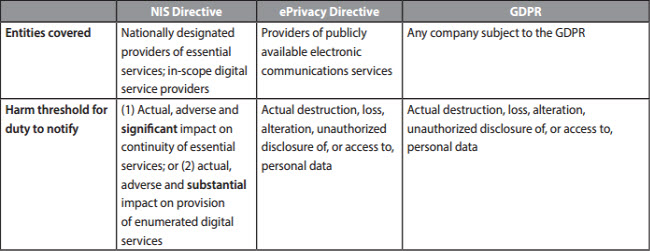

The following table focuses on overlaps between the NIS Directive, the ePrivacy Directive and the GDPR because these are broadly worded Acts likely to apply to large numbers of companies across industries. Important to note, however, is that these are not the only EU legal acts containing breach-notification requirements. Several sector-specific pieces of EU legislation require—or will require—breach notifications from participants in particular industries, for example:

- EU Regulation 910/2014 requires “trust service providers” (i.e., companies providing web certificates, e-signatures or validation of either) to file breach reports with national supervisory authorities.

- The Proposed EU Payment Systems Directive (PSD2) would require payment systems operators to report “major incidents” to the European Banking Authority.

Additionally, several countries within the EU have adopted their own breach notification laws or issued guidance on when they deem notification to either consumers or regulators is required.[4] With that in mind, the following shows potential notification overlaps between the NIS Directive, ePrivacy Directive and GDPR:

As one can see, the potential for overlapping breach notifications is significant, and given the tight turnaround times for breach reports, companies would be well-advised to engage in process-mapping well in advance of any actual breaches. A significant security event is largely crisis driven and not a good time for thoughtful analysis of reporting obligations—a bit of advance work in this phase will more than repay the investment if a significant breach occurs and notifications might have to be made.

Looking Ahead

The complexity of the NIS Directive, its potential for overlap with other EU and member state legislation and the ever-increasing fines under EU and member state legislation for compliance failures make an integrated approach to EU data protection and cybersecurity compliance more essential than ever. Alston & Bird’s Cybersecurity Preparedness & Response team on both sides of the Atlantic is closely following the implementation of the NIS Directive in EU member states, breach reporting obligations under the GDPR and the overall legal cybersecurity landscape in Europe.

If you have any questions or would like additional information, please contact Jim Harvey. The authors would like to thank Jon Filipek and Dan Felz in our Brussels office for their review of and assistance with this advisory.

[1] Formal adoption of the NIS Directive by the EU Parliament and the Council of the EU is pending; however, it is widely believed that the current draft (available here) will be adopted without change in mid- to late spring of 2016. After publication, member states will have 21 months to implement the directive into law. Within six months of implementation, member states must identify essential service operators.

[2] Unlike the GDPR, the NIS Directive must be implemented by each of the member states into its national laws.

[3] See Germany’s recently-passed “Act to Increase the Security of Information Technology Systems” (Gesetz zur Erhöhung der Sicherheit informationstechnischer Systeme vom 17. Juli 2015, BGBI. I S. 1324). A copy of the Act (in German) is available here.

[4] See, e.g., Austria: Federal Act for the Protection of Personal Data § 24(2a); Belgium: Recommendation 01/2013 of January 1, 2013, of the Belgian DPA on Security Measures to Avoid Data Breaches; Germany: Federal Data Protection Act § 42a; Ireland: Personal Data Security Breach Code of Practice issued by the Irish Data Protection Commissioner on July 29, 2011; Sweden: Personal Data Act § 38.

This advisory is published by Alston & Bird LLP’s Privacy & Data Security practice area to provide a summary of significant developments to our clients and friends. It is intended to be informational and does not constitute legal advice regarding any specific situation. This material may also be considered attorney advertising under court rules of certain jurisdictions.